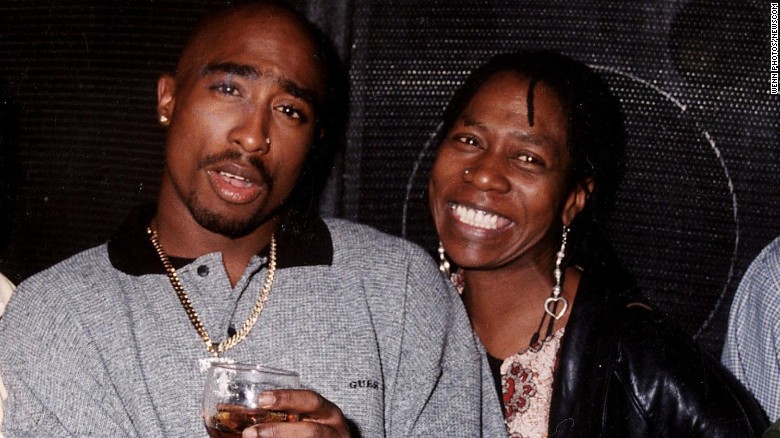

Afeni Shakur Davis, Tupac's mother, dies at 69

Tupac Shakur's mother Afeni dies at 69 ...

Story highlights

- Tupac's mother was "well-loved" community member, police say

- Afeni Shakur Davis spoke about how Tupac helped her beat drug addiction

- Police responded to a call of cardiac arrest at Shakur Davis' Sausalito home

(CNN)Afeni

Shakur Davis, the mother of one of hip-hop's most seminal and iconic

figures, has died at age 69, the Marin County, California, sheriff's

office said Tuesday.

Though

she is best known as Tupac Shakur's mom, Shakur Davis also was a Black

Panther as a young adult and an activist and philanthropist in her later

years.

Deputies

responded to a family member's call reporting "a possible cardiac

arrest" at Shakur Davis' Sausalito home about 9:34 p.m. Monday, the

Marin County Sheriff's Office said.

Shakur

Davis was taken to Marin General Hospital, where she died at 10:28

p.m., the office said. There was nothing suspicious about her death and

there's no evidence of foul play, Lt. Doug Pittman said Tuesday. An

autopsy was scheduled for later in the day.

"Sheriff's

Coroners Office will lead investigation to determine exact cause &

manner of Afeni Shakur's death," the office said in a tweet.

Shakur Davis was a "well-loved, well-respected" member of the community, Pittman said.

"Miss

Shakur has had an extensive background not only in the community but

her involvement with so many things," he said. "She's been a leader, a

person people followed. All that said about who she's been and where's

she's at now, this is a tragic loss for this community."

The

Shakur family, in a statement, said she "embodied strength, resilience,

wisdom and love. She was a pioneer for social change and was committed

to building a more peaceful world."

From drugs to arts

In a 2005 interview ahead

of the opening of the now-shuttered Tupac Amaru Shakur Center for the

Arts in Stone Mountain, Georgia, Shakur Davis recalled how her life was

almost derailed by drugs and how her son got it back on track.

Her

drug use made her so oblivious to what was happening in her life that

when someone told her in 1990 that her son -- then on the precipice of

becoming the biggest name in hip-hop -- was going to be on "The Arsenio

Hall Show," she thought the person was lying, she said.

In the mid-1980s, she was

homeless in New York and "messing around with cocaine," Shakur Davis

said. Despite the drug use, she was still coherent enough to realize

that Tupac would become a product of the streets if she didn't make

different choices.

"I was running

around with militants, trying to be badder than I was, trying to stay up

later than I should," she said in the 2005 interview.

She

decided to enroll Tupac in the 127th Street Ensemble, a Harlem theater

group, something she called "the best thing I could've done in my

insanity." They later moved to Maryland, where she enrolled him in the

Baltimore School for the Arts, and then to a small town outside

Sausalito.

It was there that Tupac confronted her about her cocaine use.

"He

asked me if I could handle it, and I said yeah because I'd been dipping

and dabbing all my life," she said during the interview. "What pissed

him off is that I lied to him."

'Pac

told the local drug dealers not to sell to her, she said, and he told

his mother to get clean or to forget about being involved in his life.

'Arts can save children'

She

got clean in 1991, she said, and when her son was gunned down in Las

Vegas in 1996, she resisted the urges to delve back into her old bad

habits. She instead founded Amaru Entertainment to keep her son's music

alive.

Later, she realized that her life -- mistake-ridden as it may have been -- might serve as a lesson to others.

"Arts

can save children, no matter what's going on in their homes," she said.

"I wasn't available to do the right things for my son. If not for the

arts, my child would've been lost."

She

provided the majority of the money to begin the $4 million first phase

of the arts center, while her Tupac Amaru Shakur Foundation hosted

poetry and theater camps for youngsters in the Atlanta area.

The family said she established the foundation to "instill a sense of freedom of expression and education through the arts."

The family said she established the foundation to "instill a sense of freedom of expression and education through the arts."

"I

learned that I can't save the world, but I can help a child at a time,"

she said, pointing out that her new life of philanthropy wouldn't have

been possible without the influence of her legendary son. "God created a

miracle with his spirit. I'm all right with that."

And as much as she credited

Tupac with inspiring her to help others, the tribulations she endured in

raising him weren't lost on the multiplatinum artist. He regularly

invoked her in his music, perhaps never as directly as in his

chart-topping song, "Dear Mama."

In it, he rapped,

"And even as a crack fiend, mama, you always was a black queen, mama/I

finally understand, for a woman it ain't easy trying to raise a man/You

always was committed, a poor single mother on welfare, tell me how you

did it/There's no way I can pay you back, but the plan is to show you

that I understand."

Shakur Davis is survived by a daughter, Sekyiwa Shakur.

.jpg)